THE NEW YORK ROCK & ROLL ENSEMBLE AND JIMI HENDRIX

“There are a funny group of coincidental songs that we made. We made an album, and we recorded a Jimi Hendrix tune called "Wait Till Tomorrow." I knew Jimi - not very well, but I knew him well enough - and he came to see us play…

He heard us playing "Wait Till Tomorrow," and he thought it was great… He got our album and was listening to it in a Band of Gypsies rehearsal. After his tune came a song called "Sing, Lady, Sing." Buddy Miles apparently liked that tune. It had a great riff….There’s no way that can translate to a magazine. But it became a Buddy Miles’s song, "Them Changes," which was a bit of an anthem in the late sixties. And we were just lying down and taking it. But we were definitely relieved of our intellectual property. And Buddy Miles turned it into "Them Changes," with Hendrix playing. And that was, you know, a major compliment. I mean, white musicians been ripping off black folks for years, it seemed just.”

Michael Kamen

Jimpress Article - Issue 82 Autumn 2006

Written by Doug Bell and Joel J. Brattin

Article originally published by and reproduced here with the kind permission of Jimpress

The New York Rock & Roll Ensemble was one of the first groups of the rock era to combine classical music tastefully with rock, using instruments and arrangements from both genres. They released five LPs during their six years together from 1966-1972. Several occurrences and meetings related to Jimi make their story of interest to Jimpress readers.

The original group consisted of Michael Kamen (keyboards & oboe), Marty Fulterman (drums & oboe), Clif Nivison (lead guitar), Dorian Rudnytsky (bass & cello), and Brian Corrigan (rhythm guitar). Both Dorian and Clif graciously shared some memories of their days in the NYRRE and of occasions when they crossed paths with Jimi. Barbara Nivison, Clif's wife, also kindly contributed details of the events; she is in the process of writing a book on the Ensemble and thus had much of the information near at hand.

Michael and Marty had both attended Manhattan's High School of Music and Art and had become friends; thus, it was no surprise when the two went on to become roommates at New York's Juilliard School of Music, where they formed the band "Emile and the Detectives." Meanwhile, Dorian arrived at Juilliard in 1964, where he was elected to the Student Council and became its president the following year. One of his duties in this job was arranging entertainment for social functions. Dorian had also played in bands back in his hometown of Toms River, New Jersey; he may have been the first Juilliard Student Council member with a rock and roll background. So, of course, he was very much interested when word came that there was a rock and roll band floating around Juilliard.

In 1965 Dorian went to Michael and Marty's apartment to audition them to play at student functions, which they did throughout the 1965-66 school year. The three became friends, and when Dorian arrived back at Juilliard for the Fall 1966 semester, he brought his gear along. At a student mixer in September, he ended up joining the Detectives for the gig, supposedly as a replacement for the regular bass player in that band (the regular bassist in fact appeared for the job, so he and Dorian shared duties that night). By chance, the producer of "The McCoys" was present at that Juilliard dance as a guest of a student, and at the end of the night approached Michael, Marty, and Dorian and advised the three of them to rid themselves of the other band members, find better guitar players, and form a band of their own.

The three discussed this, and Dorian said he knew two guitar players from Toms River, who turned out to be Clif and Brian. Dorian, Clif, and Brian were all from Toms River and had played together in bands from about 1960 - "Invictas" first, and then later briefly "There Are No Trumpets," a band that Dorian and Brian had put together in 1965. Dorian quickly brought them in for the next job – this time a Halloween Dance, again at Juilliard. This was their first gig as the "New York Rock & Roll Ensemble." For this job the band rehearsed exactly two times. In late November 1966 they rehearsed three songs for a demo session at Atlantic Records (acetates from this session still exist), and by early December the band had the news that Atlantic Records president Ahmet Ertegun wanted to give the band a three-year recording contract.

Dorian summarizes the band's good fortunes: "Yes, it's true. This is probably one of the few bands, certainly in those days, that got a major recording contract exactly the way I described. No lengthy tours and endless gigs before the contract. No image making. No clever, tedious PR. No mailing lists. None of that normal stuff one reads about. We simply rehearsed two times, played one dance job, rehearsed three songs again perhaps two times in some room somewhere, played our demo for Atlantic Records, and got a major deal."

The Ensemble released its first self-titled LP in 1968, and followed a year later with its second release, Faithful Friends (Atco SD 33-294). The group achieved enough visibility with the music from its first two LPs to catch the attention of Bill Graham, who slotted the Ensemble in as an opening act for a three-night stand at the Fillmore West in August 1969 (they played this venue for two more sets of shows in 1970).

Faithful Friends contains an early cover version of a Hendrix song, a rendition of "Wait Until Tomorrow." This version was also chosen as the A-side for Atco single 45-6671. Barbara explains the choice of this song: "Clif and Michael were roommates when Axis: Bold as Love was released. Clif bought the album and he and Michael both loved ‘Wait Until Tomorrow,’ which they started including in their live sets. They also liked ‘Little Wing’ and sometimes played that at their gigs too. They decided to record ‘Wait Until Tomorrow’ because it went over so well in concert." Dorian adds, "Michael Kamen always sang it – perhaps he chose it, but then again as a Hendrix fan perhaps Clif did. It was one of the few cover songs that remained a regular part of our sets for a long time."

The song is reasonably faithful to the original, observing the original key and tempo, and reproducing the structure of the original song in almost all respects. The NYRRE version normalizes the intro riff before the second verse; where Hendrix plays the two-bar riff only once at this point, the NYRRE plays it twice, as Hendrix does before the first and third verses. More significantly, Hendrix’s original version fades out at the three-minute mark, two bars into the seventh chorus; the NYRRE version extends to 3:48, fading out two bars into the ninth chorus. The added instrumental choruses include a sly gesture toward “Purple Haze”: the regular “Wait Until Tomorrow” chorus is built on a two-bar pattern of E and Gsus2, but the NYRRE substitutes some harmony on A in the final beats of the second measure of that pattern, evoking the underlying harmonic structure of the “Purple Haze” verse.

Following "Wait Until Tomorrow" and closing the first side of the LP is a Nivison / Kamen / Corrigan composition, "Sing Lady Sing." This is a startling song for the Hendrix fan; it bears more than a passing resemblance to Buddy Miles's "Them Changes." In fact, the resemblance verges on duplication for the main instrumental structures. It appears that Buddy's song was taken more or less straight from the Ensemble's song. This fact was noticed by some almost as soon as Band of Gypsys was released in April 1970, among them David Walley, music and arts critic for The East Village Other. In a short note in the 28 April 1970 issue of that newspaper (reproduced here), Walley remarked pointedly on the similarity between the two songs.

According to Barbara, "Sing Lady Sing" was composed during the late winter or spring of 1969: "Information given by the band to interviewers in November and December of 1968 indicated that they were to start recording their second album Faithful Friends in January 1969. When they came up with new songs they usually put them right into their sets to get the public used to hearing them so they would of course buy the albums. Faithful Friends was scheduled to be released in July 1969."

Dorian speculated on how and when Buddy might have heard "Sing Lady Sing." "Yes - - we're all still pissed off in a way about the 'Sing Lady Sing' / 'Them Changes' thing. We in the band always theorized how it came about. The NYRRE had a gig in a New York City club called Steve Paul's Scene, and Hendrix, Buddy Miles, and Sly Stone were present. At some late hour after the gig, a jam session took place with Hendrix on guitar, Miles on drums, and Clif Nivison on my bass (I don't recall if Michael played keys as well, or if others were on stage). Sly Stone wanted to play bass, but Clif refused him. I stood to the side of the stage, more impressed by the names on stage than by the music of that jam."

The date of this gig and jam is uncertain. Barbara has documentation of two dates for the Ensemble at The Scene. "The first entry for Steve Paul's Scene that I have is November 8, 1968. They had performed on the Today Show earlier that day, and a notation to jam at Steve Paul's Scene that evening was included in the itinerary. The itinerary for May 1969 indicated that the band was to play the Scene from the 22nd to the 27th of that month. I don't know if they actually played all of those dates, but that was the entry."

An 8 November date for the jam session with Hendrix is possible, as Jimi was in New York City during this period. However, as described below, material played by the Ensemble included songs from Faithful Friends, and this November date would be a bit too early for those songs to have been played. But the May 1969 dates also afford one possibility. Jimi was still in New York on the 22nd, recording "Message from Nine to the Universe" on that date. He flew to Seattle the next morning for a concert that evening (the 23rd), so we can rule out the remaining May dates, but the jam session could well have taken place on the evening of the 22nd.

Dorian continues: "Your having mentioned 'Them Changes' brings to mind that events followed quite swiftly after this very gig. Jimi or someone close to him heard us play, possibly at Steve Paul's Scene that night we jammed, and heard our live version of 'Wait Until Tomorrow,' and was aware we had recorded the song. This is how we pictured the ensuing scene: Hendrix and Miles stoned out listened to our at-that-time-current album Faithful Friends, possibly hearing all of side one, possibly placing the needle directly on 'Wait Until Tomorrow.' They of course loved our version (hmmmm), but stoned as they were, let the record play out the side. The following song, the last one on side one, is 'Sing Lady Sing,' and this knocked either Miles or Jimi, or both, out, and the rest is history.”

"I was the one who some time later wandered into some club in NYC and while there, heard 'Them Changes' being played for the first time. At first I was disconcerted by the somewhat strange version of 'Sing Lady Sing' I thought I was hearing, but then I realized it was clearly a different song, and I asked the DJ playing discs that night what this record was. He told me it was a fresh acetate just brought over for 'trial runs' by Buddy Miles. Of course I reported this to the band and our management directly afterwards, but if recollection holds, at that time one could not create a legal case for 'stealing a lick'."

Clif also remembers the jam that night. "When Jimi came to the Scene the night we were playing 'Sing Lady Sing,' he may have come to hear us play 'Wait Until Tomorrow.' At that time we ended our shows with 'Wait Until Tomorrow' and went directly into 'Sing Lady Sing' and then into 'The Star Spangled Banner.' I know this is where Buddy Miles first heard those guitar licks. I remember very vividly writing them with Michael Kamen. We were roommates at the time. I had played the opening licks for him a few days earlier, and he had written another lick to fill in the main body of the song. We left the vocal lines and words to Brian Corrigan. These were very infectious guitar licks. When I first heard 'Them Changes' I thought to myself, 'What a thief!' The words and vocal melody were Buddy's, but the heart of the song belonged to me and Mike. We asked our lawyer about it and his answer was 'you can't copyright a guitar lick, only chords, words, and melody lines.' So we didn't pursue it. But it always bugged the shit out of me that he stole our guitar licks. However, it was quite a kick to hear Jimi play my guitar licks. God knows I've played enough of his. Buddy will most likely deny he stole anything.”

"At the Scene that night Michael Kamen talked to Jimi, and Jimi said he liked our version of 'Wait Until Tomorrow.' The jam session later that evening is very hazy to me. I played bass (Sly Stone wanted to play bass but I wouldn't give it up). Buddy played drums, although at the time I didn't know who he was (Jimi and 'Them Changes' made him famous). My overall recollection of Jimi from that jam is that he did a lot of strange moves and played so loud it made your ears bleed. This is all I remember of the jam."

Also interesting is Clif's mention of "The Star Spangled Banner." Clif gives more details about the history of this song in the Ensemble's repertoire. "Marty did a comic (and very condensed) version of ‘The Star Spangled Banner’ while he was at Juilliard in 1966, before we ever formed the group. At some point in our earlier concert and club shows we decided to end our concert with a very short and psychedelic version of ‘The Star Spangled Banner.’ We would play the first six notes of ‘The Star Spangled Banner’ (the most famous part) and then launch into a wild series of feedback / explosions / whammy bar effects / string slides / electric organ smashes (somewhat similar to the bomb explosions that Jimi did in the middle of his ‘Star Spangled Banner’). Then we would all crescendo to a high note and play what sounded like the last six notes of ‘The Star Spangled Banner.’ Those last notes were slightly changed to give a comic and mind- bending end to the cacophony. One article mentions it on December 31, 1968. Note that we did not know that Jimi did ‘The Star Spangled Banner’ until we heard his performance at Woodstock from the summer of 1969. I can't comment about whether Jimi got the idea from us. He may have realized the power of playing ‘The Star Spangled Banner’ and tucked it into his subconscious so that it came out later."

Barbara was able to add a few details documenting the performance of this song by the Ensemble. "The first written entry alluding to 'The Star Spangled Banner' was in the Hartford Courant (Saturday, January 4, 1969). They performed with Arthur Brown on December 31, 1968 in Hartford, Connecticut, which was the performance the article was written about. The article was written by Jackie Ross, 'Teens 'N' Twenties' editor for the paper. The title of the article was 'Ensemble Quenches Brown "Fire".' Quotation as follows: 'With imagination the Ensemble did everything for the audience but raise the flag and salute it, and in their final arrangement they almost did that. Only the most imaginative composers can take a rock song bemoaning a lost romance and turn it into something similar to the national anthem.'

"The next engagement was at Lebanon Valley College, Pennsylvania on April 18, 1969. The article appeared in the college paper La Vie Collegienne, Vol. XLV No. 20, dated April 24, 1969, written I believe by Dave Bartholomew. Titled 'N.Y. Rock and Roll Ensemble Receives Two Standing Ovations,' quotations include: 'The last number in the first set was amazing. Called "Sing Lady Sing" it was an excellent example of the ad-lib rock-psyc time.' He then spoke about the drummer and went on to add, 'As a bit of comic relief they broke into the first few bars to "The Star Spangled Banner" and then returning to the ad lib solo of the lead guitarist Cliff Nivenson [sic]'."

It is evident that the Ensemble developed their version of "Banner" independently of the Hendrix version. Whether Jimi was influenced by their arrangement of the song is uncertain. His live performances of this song date back to the autumn of 1968, predating the jam at the Scene described above. Barbara adds, "We never knew all the people who came in to see the NYRRE. Once I turned around and Janis Joplin was standing behind me with her friend listening to the band at 'Wheels' in New York City. The band was on stage playing and people came and went. So there is actually no way to know exactly when Hendrix first saw the NYRRE." As Barbara points out, it's possible that Jimi witnessed an earlier example of the Ensemble version of “The Star Spangled Banner” than the one that night at the Scene.

Brian left the New York Rock & Roll Ensemble in 1970 after the third LP Reflections; the remaining four continued as the renamed "New York Rock Ensemble" and recorded the excellent Roll Over (1971) and Freedomburger (1972). Clif and Marty left the band in July 1972 and went on to become producers at Scepter Records / Opal Productions. In the autumn of 1972 Michael formed a "solo" band, with Dorian and five new members, called "Michael Kamen and New York Rock," but the end was in sight. The group finally disbanded for good around September 1973.

Dorian played afterwards in numerous bands as a bass player, simultaneously continuing his classical work as a cellist and composer. Since 1995 he has lived in Germany, playing both bass and cello and composing quite a bit for theater productions. His “Costa Blanca Suite” for cello solo, rock band, and orchestra will premiere in Spain in September 2006. Clif never stopped playing the guitar; in the late 1970s he formed "Borzoi," a hard-rock band that had considerable success in the New Jersey-Pennsylvania club scene, and afterwards played in numerous bands up to the present day. He currently lives and plays in Florida, and he remains a world-class guitar player. Brian Corrigan left the band just before Roll Over was recorded. He attempted a solo career directly afterwards that did not succeed, and dropped out of musical activities for a long time. Recently he has again become active, this time in the Christian music scene, and is currently preparing demos of songs he composed. Dorian is helping him with this project.

Marty Fulterman worked for a short time as a writer / producer in New York City after the Ensemble broke up, and then moved to Hollywood, where he changed his name to Mark Snow. His impressive resume as a TV composer includes the score for the popular television show The X-Files. Grammy winner Michael Kamen also found great success in Hollywood; the list of films for which he composed music is extensive, including the Lethal Weapon and Die Hard movies, The X-Men, and dozens of others. Sadly, Michael died in 2003.

Harmonic / Structural Analysis of “Sing Lady Sing” and “Them Changes”

The close resemblance between the song “Sing Lady Sing” by the New York Rock & Roll Ensemble and “Them Changes” by Buddy Miles and the Band of Gypsys is more than coincidental. Analysis of the two songs clearly shows that the composer of “Them Changes” borrowed heavily from the earlier song - - to such an extent that one could certainly call it plagiarism.

“Sing Lady Sing,” written by Clif Nivison, Michael Kamen, and Brian Corrigan, was recorded by the Ensemble in early 1969, and released on their album Faithful Friends later that same year. “Them Changes” was recorded by Buddy Miles (with Billy Cox on bass and Wally Rossunolo on guitar) in early 1970 for his studio album Them Changes, and live versions by Jimi Hendrix, Buddy Miles, and Billy Cox were recorded at each of the four shows the Band of Gypsys performed at the Fillmore East on 31 December 1969 / 1 January 1970. The Band of Gypsys album, including the last of these four live versions of “Them Changes,” was released in April of 1970, with Buddy’s album Them Changes appearing shortly before that.

Buddy Miles is credited as the composer of “Them Changes” on both the Buddy Miles and Band of Gypsys releases; when Jimi introduces the version that appeared on Band of Gypsys, he says “Buddy wants to do a thing he wrote called ‘Them Changes.’” However, the fine “Transcribed Scores” version of Band of Gypsys, published by Hal Leonard in 1997, erroneously gives the title as “Changes,” and credits Jimi Hendrix as the composer.

In the analysis that follows, we move back and forth between the two songs, always considering the original composition by Nivison, Kamen, and Corrigan first. We look at the introductory riff, the pentatonic riff, and the basic riff (from which both the verses and the choruses derive), and then move to a more general consideration of form. We exclude from consideration here the lyrics and vocal melody, confining the examination to riffs and structure.

“Sing Lady Sing,” in the key of E, opens with a two-bar introductory riff, repeated twice for a total of four measures. The first measure is based on the A pentatonic minor scale, using the pitches E, G, A, C, and A. (Notice that the first three notes of the riff are common to the pentatonic minor scale in E, a closely-related key.) The second measure is precisely the same both rhythmically and melodically, but the pitches are shifted down a perfect fourth, to B, D, E, G, and E; these pitches, in E pentatonic minor, establish the key of E.

“Them Changes” is also in the key of E, and it, too, opens with a two-bar introductory riff, repeated twice for a total of four measures. The riff itself is at least superficially quite different, though both introductions serve similar harmonic purposes. The first measure features a G5 diad resolved to a D3 diad, followed by a D5 diad resolving to an A3 diad— essentially a move from D to A, establishing the same harmony as the first measure of “Sing Lady Sing.” In the second measure, the guitar moves from A up to D, E, and G; as in “Sing Lady Sing,” these pitches, from the E pentatonic minor scale, establish the key of E.

After the four-bar introduction, “Sing Lady Sing” moves into a distinctive two-measure pentatonic riff, played in unison by both the bass and the guitar, and based on the pentatonic minor scale (see figure 1a). The first measure of this riff is based on the A pentatonic minor scale (A C D E G): two eighth notes on E, an eighth note on G and two sixteenth notes on E and D, an eighth note on C, and an eighth note tied to a quarter note on A. The second measure is rhythmically identical, but (as with the introductory riff) the pitches are shifted down a perfect fourth; these pitches, in E pentatonic minor (E G A B D), establish the key of E. This pentatonic riff is played twice, for a total of four measures.

Like “Sing Lady Sing,” “Them Changes” also enunciates a distinctive two-bar pentatonic riff after the introduction. Played in unison by the bassist and guitarist, it is virtually identical to the “Sing Lady Sing” riff (see figure 1b).

Like the riff to “Sing Lady Sing,” the riff to “Them Changes” starts with two eighth notes on E, an eighth note on G and two sixteenth notes on E and D, an eighth note on C, and an eighth note on A. The final beat of the first bar of the “Them Changes” pentatonic riff is very slightly different rhythmically, though: where the original riff sustained A for the final beat, “Them Changes” offers a dotted eighth followed by a sixteenth note on A. The second measure of the “Them Changes” riff shifts the pitches down a fourth to E, like “Sing Lady Sing,” again closely following the rhythm and pitches of that song; in the final measure, the only difference between the two riffs is that in “Them Changes,” there is no tie connecting the E on the fourth beat to the one on the upbeat of the third. The pentatonic riff in “Them Changes,” like the one in “Sing Lady Sing,” is played twice, for a total of four bars.

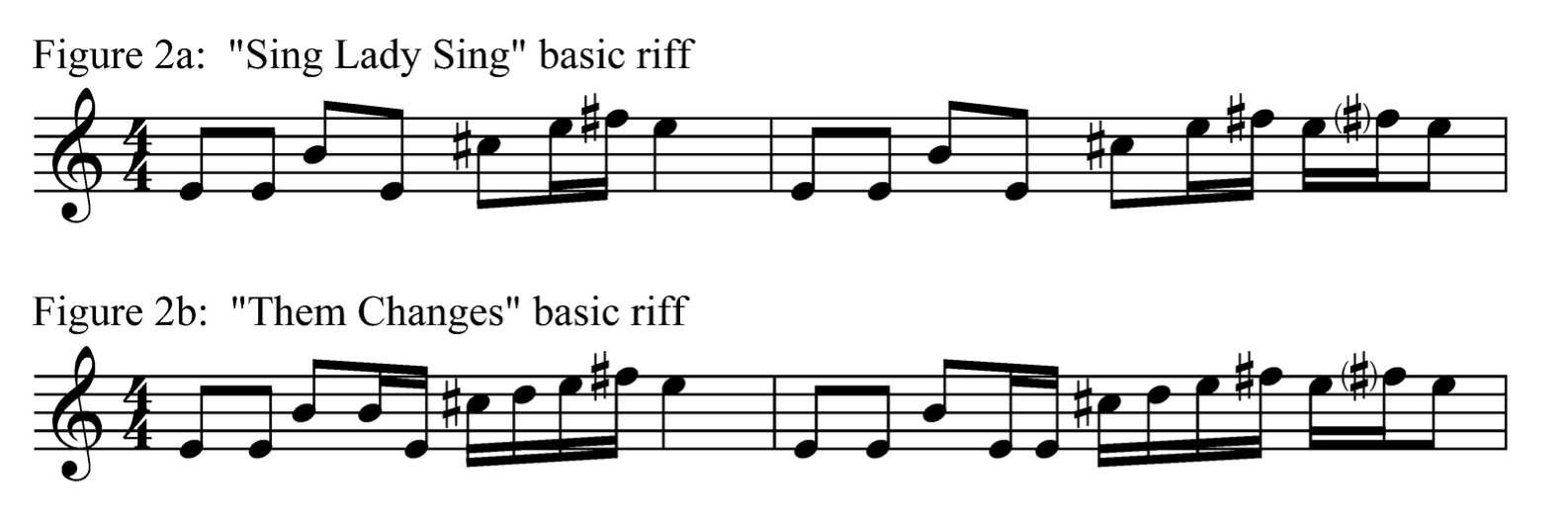

After the four measures of pentatonic riff, “Sing Lady Sing” moves to another two-bar phrase we will call the basic riff (see figure 2a), as it is the basis for so much of the rest of the song. Again, the bass and guitar play this riff in unison. The first measure of the basic riff, which is in the key of E, begins with two eighth notes on E, eighth notes on B and E, an eighth note on C# with sixteenth notes on an E an octave higher than the initial one and an F# a whole-step above that, and a final quarter note of the higher E. The second measure of the basic riff is identical to the first, with the exception of the final beat, where we now have sixteenth notes on E and F# and a final eighth note of E. This basic riff uses the major 6th (C#) on the third downbeat of each measure, and the major 9th (F#) just before the fourth downbeat (and just after it as well, in alternate measures). In the structure of “Sing Lady Sing,” we have two statements of the basic riff (four bars) after the pentatonic riff, followed by the first verse (four more iterations of the basic riff, for eight measures).

“Them Changes” also moves to a two-bar basic riff played by the bass and guitar. It is almost identical to the one in “Sing Lady Sing.” The bass riff, played in second position with open notes, offers minor variations in the second half of the second beat of each measure; the guitar riff, played in seventh position (utilizing open strings for the low E) also substitutes sixteenth notes on B and C# for the eighth note on C# at the third downbeat of each measure (see figure 2b). Just as in “Sing Lady Sing,” we find two statements of the basic riff (four bars) after the pentatonic riff, followed by the first verse—sung, like the verse of “Sing Lady Sing,” over more iterations of the basic riff, though in “Them Changes” the riff is played eight times, for a total of sixteen bars.

After the first twenty measures of “Sing Lady Sing,” then, we’ve had the introduction (four bars), the pentatonic riff (four bars), the basic riff (four bars), and the first verse (eight bars of the basic riff). After the first twenty-eight measures of “Them Changes,” we’ve had the introduction (four bars), the pentatonic riff (four bars), the basic riff (four bars), and the first verse (sixteen bars of the basic riff).

The pentatonic and basic riffs for “Sing Lady Sing” and “Them Changes” make up most of the remainder of the two songs; these two riffs are the basic building blocks for both songs.

After the first verse of “Sing Lady Sing,” we move to the first chorus, which begins with three statements of the basic riff, followed by two beats of E, two beats of D, and the first measure (only) of the pentatonic riff. The second verse of “Sing Lady Sing” is the same, structurally, as the first: eight bars of the basic riff. The second chorus is similar to the first chorus, but not precisely identical to it. After the seventh measure (with two beats of E and two of D), there are three measures of A, followed by another measure of 2/4 (we’ll consider this a half-measure) on A, a crashing E chord on the next downbeat held for six beats (one and a half measures), a beat of silence, and the exclamation “hey!” on the next beat. Two more statements of the pentatonic riff follow, and then the solo, performed over two statements of the pentatonic riff and two statements of the basic one. The third verse and third chorus are precisely the same structure as the second verse and chorus. The ensemble plays the pentatonic riff twice more, and then a four bar outro, again based on the pentatonic riff.

After the first verse of “Them Changes,” we move to the first chorus, built from two statements of the pentatonic riff followed by two statements of the basic one. The second verse is, again, sung over sixteen bars of the basic riff. The second chorus is abbreviated: it’s just four bars long (two iterations of the pentatonic riff, without the basic riff to follow). A solo and interlude follow: four bars of stop-rhythm, followed by many iterations of the basic riff. (On the original Band of Gypsys release, the solo and interlude are played over 72 bars of the basic riff. Some—including the editors of the Hal Leonard “Transcribed Scores,” and the editors of From the Benjamin Franklin Studios, 2nd edition—have suggested that the master tape is edited here, though no more complete tape has surfaced. The versions of “Them Changes” performed at the other three Fillmore East shows are significantly longer than this one, however; the three earlier versions give solo / interlude passages of 96, 190, and 128 measures, respectively.) After the final chorus, abbreviated like the second one, the song ends with a free-time outro and cadenza on E9.

Well over 90% of “Them Changes” is taken up by the pentatonic and basic riffs: excluding the four-bar intro, the four measures of stop-time introducing the solo, and the brief outro cadenza, there’s simply no original structural material here.

Doug Bell and Joel J. Brattin

The authors wish to thank John Delorey and Ken Voss for their kind help in preparing this article. Special thanks to Barbara Nivison, Clif Nivison, and Dorian Rudnytsky for their generosity in providing much of the background material.

Article originally published by and reproduced here with the kind permission of Jimpress.co.uk

Jimpress Issue 82 Autumn 2006